Is God Merciful?: The Difference between the Impassibilist and Passibilist Positions

Snips from the Diss (2)

Here is another snippet from my dissertation, handling the question How do the traditional/impassibilsit and contemporary/passibilist positions on mercy of God really differ? And also, *why* do they differ? It also determines what those who hold the traditional position need to do in answer to the contemporary position..much of which I’m trying to do in my dissertation!

I’d love your feedback and critique!

The difference between the traditional and contemporary positions is as clear as it is simple–as is the (likely) primary cause of this difference.

Beginning with the former, these positions divide on the question Whether God is or is not merciful. This dividing question is intended properly/formally, viz., the affirmative proposition signifies a judgment which composes mercy as a whole (or at least in part) to God, whereas the negative signifies one which divides the same from him. The contemporary position holds the affirmative of this contradiction, and thus that some true proposition can be proper, that making a proposition true still manages to retain propriety regardless of, say, any other prior negative judgment (e.g., removing the bodily aspect of mercy) and/or later adjustment (e.g., changing the mode of signification). The traditional, by contrast, holds the negative, and therefore that no true proposition can be proper, that making a proposition proper has ipso facto sacrificed truth at the altar of propriety. Thus and in the simplest terms, the contemporary is so bold as to posit mercy in God, whereas the traditional stands resolute and refuses to do so.

There is another way to approach this difference, and which renders it even clearer: someone’s position is traditional or contemporary depending upon whether he assents to or dissents from a certain negative judgment. That judgment removes the concept mercy from God; and importantly, it does so not just partly, but wholly.

We must underline this wholly, and differentiate from e.g., Thomas’s negative judgment which removes only part (the genus) of the concept knowledge (scientia), while still retaining the other part (the specific difference)--which thus results in God having knowledge properly and formally, i.e., as regards the species of knowledge. Propositionally, we say that God is sciens not simpliciter, but only secundum quid, namely according to its species; and likewise that he is not sciens secundum quid, viz., according to its genus.

By contrast, the negative judgment whose assent or dissent constitutes the traditional or contemporary positions respectively, entirely removes this concept mercy both genus and specific difference, leaving no remainder. One could signify such an all-encompassing judgment more colloquially by God having nothing of mercy, or nothing of mercy falling in God; or scholastically, by God not being merciful simpliciter (without qualification and period!). Someone holds the traditional position only if he assents to this negative judgment; if he dissents therefrom, he holds the contemporary; if he has not yet determined this question or to the degree he is fuzzy on it, then he will almost inevitably lapse to the contemporary. And it is worth going on and making perfectly clear that there is no third option here, given the law of non-contradiction. If the negative is true, then any true affirmative could not signify a judgment composing this concept; indeed, such an affirmative would be the other part of the very same contradiction whose negative is at hand. Accordingly, one either assents to that negative and thereby foregoes all ability and swears off every inclination to ever compose this concept to God; or he dissents from that negative and thus preserves if not his truth, then at least his intellectual “rights” to do so.

Still, we ought to add that the contemporary position can be distinguished into two subpositions. For there are some who remove none of the concept, but posit the whole into God: that God is merciful simpliciter. Yet there are others who remove part of the concept, and posit the other into God: that God is merciful secundum quid (albeit also not merciful secundum quid). (As an aside, this latter bears much resemblance to, and sometimes is the same as, positions found in the early modern period.) In light of this, one could speak of a “stronger” and “weaker” contemporary position, the former which is entirely opposed to the traditional position, and the latter which is opposite only in part.

Yet at any rate, there is thus extreme need for showing that this negative judgment is true, as the entire traditional position would be rendered insufficient if this judgment were false; but by the same token, the entire contemporary position will be manifest as false if the same judgment is true. And with these stakes, it remains incumbent to not just show this judgment true through authorities–which is easy, as abundant testimonies from the fathers can be supplied, usually to the effect that God does not have any passions (mercy thus included). Rather, one must also use reasons or arguments, and not just generate plausible arguments which result in opinion on this matter, but give demonstrative reasons which result in assent and scientific certainty. Thomas has begun this latter task in SCG I c 89; but acquiring a healthy amount of scientia about the truth of the negative judgment remains the initial and sine qua non task of every theologian who would consider mercy of God.

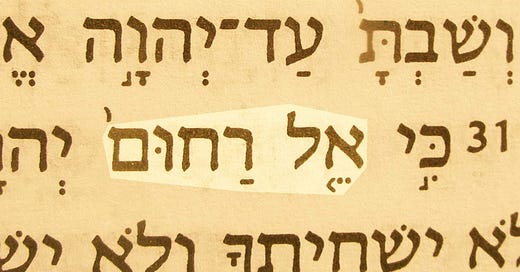

To be sure, this task of showing it true is rendered very difficult, but also the more necessary, by holy Scripture. And this brings us to the (likely) primary cause of the difference between the traditional and contemporary positions: viz., whether or not they understand holy Scripture secundum litteram. This is worth considering at some length, for between the traditional and contemporary positions is waged not just a battle over doctrine of God, but also a battle over holy Scripture–

As we consider holy Scripture, we find therein many sayings whose ad litteram sense is the proposition that God is merciful–indeed, which is the same proposition as the affirmative of the above contradiction. Notwithstanding this, the traditional position stubbornly refuses to understand according to the letter (intelligere secundum litteram): i.e., it does not understand reality as so; it does not hold the judgment which ought to be signified by such a proposition (viz., which composes this concept to God) as true; etc.

What then does the traditional position do, positively speaking? Merely one of two things: it either (1) concedes this ad litteram sense and proceeds from there; or (2) it argues a different (and often additional) one and then understands according to that. Both of these we will see below; but speaking here only to the former (which the majority of tradition follows), the scriptural saying is then additionally interpreted allegorically–for regardless of the letter, any true judgment will be altogether otherwise. Yet still, “we must attribute mercy to God maximally,” i.e., using the strongest or most positive true judgment possible, as Thomas reminds. Accordingly, the traditional position seeks the maximal true judgment which can be used to interpret the letter–which, we will eventually find, involves an analogy of proportionality: just as a man from his mercy e.g., saves, likewise God from his love. Although there are many other options on this line, this is the “best offer” which the traditional position can muster.

By sharp contrast, the contemporary position seizes upon the letter and “takes these sayings literally,” i.e., understands according to this ad litteram sense. Accordingly, the contemporary understands such as signifying judgments positing mercy in God. On this line, the saying “mirrors” its intellectual judgment, and holy Scripture is taken at face value: God being merciful not only means what it says, but reality is as it says.

Understandably, the contemporary position also takes advantage of holy Scripture and argues two points against the traditional. First, it argues the falsehood of the traditional’s negative statement, viz., that God is not merciful simpliciter. Each and every time holy Scripture reads God being merciful, is yet another opportunity and even demand to pound away at the negative judgment God not being merciful–proof positive of its falsehood and the traditional position’s error. But then second, it protests the insufficiency of the traditional’s positive statement(s), even its “best offer” (analogy of proportionality). Although forced to admit that the traditional offers at least a true judgment as an interpretation of the scriptural sayings, the contemporary hastens to add that the interpretation is insufficient–not just insufficient given reality (in that God really is merciful), but insufficient given the letter!

Indeed, this latter issue is most acute. The contemporary feels that the traditional does not do justice to the letter. It will argue e.g., as follows:

These scriptural sayings are differentiated from others which are metaphorical, like God being a rock or having a hand. Unlike these, God being merciful is not found infrequently; and more importantly, neither is there any conventional sign that it must be understood otherwise than it says.

These sayings are the same as those which are understood properly (also by the traditional position): God being merciful is the same as e.g., him being loving. Accordingly, if these scriptural sayings are both differentiated from metaphorical ones (God having a hand) and rendered the same as proper ones (God being loving), then they ought to be understood also properly–albeit perhaps removing the bodily aspect of having mercy.

The prophets hold up God being merciful for us to imitate, whereupon something in God must be being imitated: “be ye merciful, just as your Father is merciful” (Luke 6:36).

No argument taken from holy Scripture can sufficiently conclude God not being merciful. More, no argument can make us even suspect that this is true.

Prophets use these sayings as principles of argument for many other conclusions, and further such sayings must be understood properly in order to sufficiently argue these conclusions: God being merciful, therefore he forgives does not conclude unless the principle is understood properly.

Prophets even use many other sayings to argue God being merciful as their conclusion. They could not do this if it must be understood otherwise than it says.

To these and similar arguments, the traditional position cannot really respond from holy Scripture. It must admit that the contemporary runs with the grain of the letter, and must make clear that it is not unaware of all the splinters which are acquired from running so determinedly against the grain. Still, the traditional can and does respond in three ways.

First, the traditional can and must scientifically demonstrate the truth of the negative judgment. If the contemporary is armed to the teeth with the scriptural sayings, then the traditional must respond, if not in kind, at least in equivalent measure with philosophical demonstrations. Indeed, although multiplying authorities from the fathers is helpful and desirable, we cannot expect those who hold the contemporary position to reject it except upon strict demonstration–as nothing else but the absolute certainty of science arising from such demonstration (and indeed many demonstrations) is sufficient for anyone to read the scriptural God being merciful, but assent to the judgment that he is not. It only becomes remarkable that someone is unmoved when they read e.g., that God has a hand, and does not hold that he is a body, if we forget that he holds God being incorporeal as true. Likewise, it would be remarkable indeed if someone read that God is merciful, but remained immobile and held that he is not, unless he were certain that God being impassible is true, unless he were certain that in God are no passions (mercy being among them) either according to genus or according to specific difference.

Yet beyond philosophical demonstration, the traditional position can and must maximize its positive statement how God is (said) merciful–or else they cannot offer a sufficient alternative to the contemporary position which so enjoys the delight of composing mercy to God. Indeed, far too often representatives of the traditional position content themselves with saying what is not (e.g., that God is impassible), or with destroying error (e.g., that God is merciful), and never say what is, what (for lack of better terms) lies behind this proposition God being merciful and dwells in the land of judgments. Needless to say, maximizing the traditional position’s positive statement includes not just giving any judgment, e.g., that God is not cruel, but even the strongest judgment or fullest explanation, namely analogy of proportionality–that just as a merciful man saves, just so God. And indeed it includes then expanding that analogy to the fullest degree (e.g., …just so God from love), enclosing each and every of the network of judgments involved, in order to constitute the entire intellectuality within the mind, when God being merciful comes out the mouth. And finally what is more, it includes maximizing the rational justification for “saying one thing when thinking another,” which includes (1) giving the whole fittingness (ratio convenientiae) for saying God being merciful when thinking e.g., that he saves; but also (2) explaining when in reality God only saves, why one would ever say at all that he is merciful (Augustine’s ratio quare ita dictum sit)–especially when such saying occasions the very false judgment of the contemporary position!

Third and indeed related to exactly this, the traditional position can and must explain the phenomenon of holy Scripture, and justify the ad litteram sense of its relevant sayings, the very proposition of the contemporary position. Here too contemporary representatives of the traditional position must be confessed as insufficient, so rarely explaining why Aristotle’s God has so–and so otherwise–been said in holy Scripture. As we will see, such an explanation includes, inter multa alia, the prophet’s use of dialectical propositions for arguing true conclusions. Nothing else does justice to the concrete phenomenon of holy Scripture; and although such an explanation will not be agreeable to someone who holds the contemporary position, it does do justice to the letter, and provides an alternative explanation for the concrete data, an alternative explanation besides God in reality being merciful. That explanation, in fact, is equally as sufficient as the explanation which the contemporary position holds, namely that the sayings are proper but as such true. Such an alternative and equally sufficient explanation removes the sting from the “biblicist” arguments which generate the contemporary position, and reverts both sides to the neutral ground of philosophical demonstration to determine the question whether God is or is not. And there, it is no contest.

Hi Dr. Hurd, I interacted with Thomas and mercy in my dissertation so this post is of interest to me--thank you! I have some questions and I would like to post an interaction. Can you help me with further clarification of this paragraph: "We must underline this wholly, and differentiate from e.g., Thomas’s negative judgment which removes only part (the genus) of the concept knowledge (scientia), while still retaining the other part (the specific difference)--which thus results in God having knowledge properly and formally, i.e., as regards the species of knowledge. Propositionally, we say that God is sciens not simpliciter, but only secundum quid, namely according to its species; and likewise that he is not sciens secundum quid, viz., according to its genus." I think this is a key to the article and I am not following the Latin as well as I should. (???)