One of my favorite quotations from Thomas is that every action and passion of Christ is not only a saving reality, but also a signifying one (see his sermon, The Boy Christ). The whole of it, both things he does (actiones) and things done to him (passiones), is not just redemptive, but also revelatory. For this reason, all the interactions of Christ with others must be carefully considered as to what such signify, especially involving revelation of Christian mysteries.

We are speaking here of Thomas’s doctrine of spiritual sense, which is that sense or those truths which arise from signifying realities, in contrast to signifying words (or letters). For Thomas, many (but not all) realities enclosed in the letters of holy Scripture are not only themselves signified by such letters, but also themselves signifying. And in that all the realities of Christ himself are also signifying, this makes the writings of the Four Gospels, insofar as they signify Christ, to have beyond this spiritual sense as well.

Thomas further alerts that of the four authors, especially John writes with the intention or final cause to advert us to these realities as further significant beyond the letters. We thus find throughout John’s Gospel what Augustine called “lightning letters,” like when Nicodemus comes to Christ and John says weightedly: “and it was night.” Augustine’s own example is the spear, which John says opened the side of Christ: opened-outward is a strange word to signify the piercing or pushing-inward of Christ’s flesh. Here then is a lightning letter: John is adverting us to the flesh of Christ as a significant reality; insofar as his flesh is pushed in, the door is being really opened unto us of eternal life.

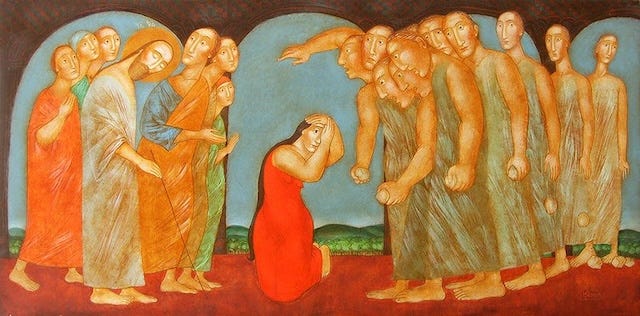

So John writes and thus signifies the real history of Christ’s life, but he especially does this so as to advert to its signification. This makes the book particularly rich or dense in spiritual sense–something which Thomas’s commentary thereon especially extracts. One of my favorite passages (and where Thomas underlines other “lightning letters”) is John 8, involving the woman caught in adultery. Specifically, I am referring to verse 9: “There remained only Jesus and the woman standing there” (John 8:9), “namely,” Thomas says, “Misericordia and Miseria,” Mercy and Misery incarnate, we might say. Thomas in fact is quoting from Augustine, whom he includes in his Catena: “two remained,” Augustine said, “Miseria and Misericordia.” (One might recall Pope Francis also took his cue from this quotation in his Apostolic Letter Misericordia et miseria.) As Thomas re-ups this quotation, he is flagging that these two realities or (all together) this one scene God providentially made to signify the mode how God himself stands to us sinners. And Thomas’s commentary attempts to issue its sense or interpretation. Let us follow him.

Once again, John 8:9 reads: “There remained alone Jesus and the woman standing in the midst.” If we were considering its literal sense, i.e., what arises from its signification in words, then we have the historically true judgment that Christ remains with the woman standing. Continuing with the literal sense, Thomas then handles some issues involving it, namely which arise because we read that Christ and the woman are alone. If alone, Thomas questions, then how is the proposition that the woman stands in the middle also true?

Thomas gives two possible resolutions to this dubium. One is that the woman stands in the middle of Christ’s disciples. Accordingly, the predicate alone excludes only the Pharisees. This would be the literal sense of alone, and indeed the proper literal sense. But alternatively, Christ and the woman indeed are alone as excluding all others–and John is speaking metaphorically of in the middle. The woman doubts about whether she will be absolved or condemned. Recall that doubt for Thomas is a certain middle between yes and no. This would still be the literal sense of in the middle, but now the improper or metaphorical literal sense: it is not that she is in the middle of persons, but that she is afraid and in the middle of two outcomes. We might translate today that there remained alone Jesus and the woman afraid, as her judgment still hangs in the balance.

Indeed, a moment earlier Thomas had given the literal sense as to why the woman would be in the middle i.e., afraid: because one by one the Pharisees left because they had sin; Christ, who has no sin, remains with her alone and as her judge. This makes the woman afraid, for Christ had said that he who has no sin shall cast the first stone. Upon her now being alone with Christ without sin, she feels threatened by him and believes that she is about to be stoned by him.

And here of course we begin to see the spiritual sense of this reality, in the confrontation of the Holy with the Unclean, which always expects its own destruction, and whose destruction the Accusers urge and incite. Of course, in the fears produced by our own minds and then the blinding we undergo by so many accusers, so easily do we lose sight of truth: the always prior mercy of God. It is precisely for this reason that God, in his kind providence, has given us significant realities which place before our eyes and ears sensible signs of saving truths.

Thomas alerts to this in his own quiet way: “There remained only Jesus and the woman standing [in the midst], namely Mercy and Misery.”

For Thomas, Christ and the woman are two divinely intended signs or symbols. Christ is said to be seated, to signify him as judge; the woman is said to be standing, to signify she is being arraigned; and she is said to be standing in the middle, Thomas notes, to signify that the question “whether she will be absolved or condemned” is in doubt, caught between absolution and condemnation. The Pharisees have given many objections arguing in favor of condemnation; her own person expects and argues this, which is why she is afraid; now Christ’s actions will determine the question and resolve our doubt as to its true response. This signifies the mode how God handles us sinners at the very end of days, when we stand before the judgment seat afraid. And what we find, Thomas says, is nothing else but Misery face-to-face with Mercy–and the outcome of this meeting we happily see here in story fashion, so we can remember it in our soulish ways.

Continuing with the spiritual sense, John the Evangelist himself had already adverted us to this theme initially by saying in verse 1 that Christ went unto the Mount of Olives: here again is a lightning letter, “because oleos in Greek is misericordia in Latin,” Alcuin notes also in the Catena. Thomas picks this up in his own comment, and notes that such “befits the mystery” which was going to be revealed, because “as Augustine says, where was it [more] fitting for Christ to teach and manifest his mercy except on the Mount of Olives…the olive signifies mercy.”

It continues. Christ then descends into the temple of God, and begins to teach–through his actions, as we come to find–the true nature of divine mercy, especially in its interplay with divine justice. Hence it is written, Thomas says, that “we received, God, your mercy in the midst of your temple” (Ps. 47:10). There Christ sits down, literally so that his doctrine would be easier grasped–although this corporeal sitting also spiritually signifies his condescension from God in incarnation, so that Christ being visible we are more easily taught about divine truths, Thomas says: Christ makes sensible the nature of divine mercy, as he symbolically acts-it-out for our senses.

The rest of Thomas’s commentary on this section is complex, and we will have to treat it more fully another time. But one thing to note briefly is that the issues here are not entirely about mercy; but also include justice. Following basic medieval impulse represented well by the Lombar IV Sent d 46, Thomas looks for the ways in which mercy and justice are both present in various ways. Hence Thomas notes that overall the Pharisees were testing Christ about two issues: about “justice and mercy.” They were “wanting to know whether he on account of mercy would recede from justice.” Thus they crafted the Woman’s sin “in three modes, which they intended to move Christ from his kindness.” In Alcuin’s phrase, they “asked him, not that they may learn, but that they may bind their nets around the truth.” But what they intended for evil, Christ seized as a further opportunity to manifest the truth. Hence the Evangelist records both how Christ “in responding” in truth and his teaching “preserved both,” first justice and second mercy--Thomas’s division is taken directly from Augustine.