“The Divine Scriptures, raising us from earthly and human [sensory] knowledge unto divine and heavenly, descended even to those very words which the most simple habitually use among themselves. Thus, those men through whom the Holy Spirit spoke did not hesitate to perfectly put in their books names of those [things] which those who are already wiser understand are extremely far removed from God.”

—Augustine

The vast majority of holy Scripture employs metaphors of various sorts. These are the primary tools which the prophets and apostles used to lead us into truth.

Accordingly, understanding metaphor is thus essential to interpreting holy Scripture and actually apprehending divine revelation therein. This is why someone like Maimonides–a master interpreter of scriptural metaphors–will go so far as to say that the key to interpreting everything written by the prophets lies in understanding their metaphors.

What then even is a metaphor? And likewise, why is it the main biblical tool?

What Is a Metaphor: Definition and Parts

Starting with the former question, metaphor goes by many names–all of which variously insinuate its definition. One name is, of course, metaphor–a transliteration from the Greek μεταφορά, which means something bearing across i.e. to another. Another name is allegory, from ἀλληγορία, which means something forthtelling another. A third (less common) name is anagogy, from ἀναγωγή, which means something guiding beyond i.e. itself unto another.

Many other names and issues could be considered here, but from carefully considering these three names, we can easily derive what a metaphor is. It is nothing else except one put for another. This is the usual and most fitting phrasing of the definition; but another phrasing is something said, but another understood.

This definition, which is common to classical philosophers and theologians, also underlines that every metaphor has just three parts: “the one”; “the another”; and “the putting,” so to speak. This further alerts us that we really have just three questions to consider, when it comes to any metaphor: (1) what is the one?; (2) what is the another?; and (3) what is the reason why this was indeed put for that? All three questions are important, but the second and third usually take the most time and focus.

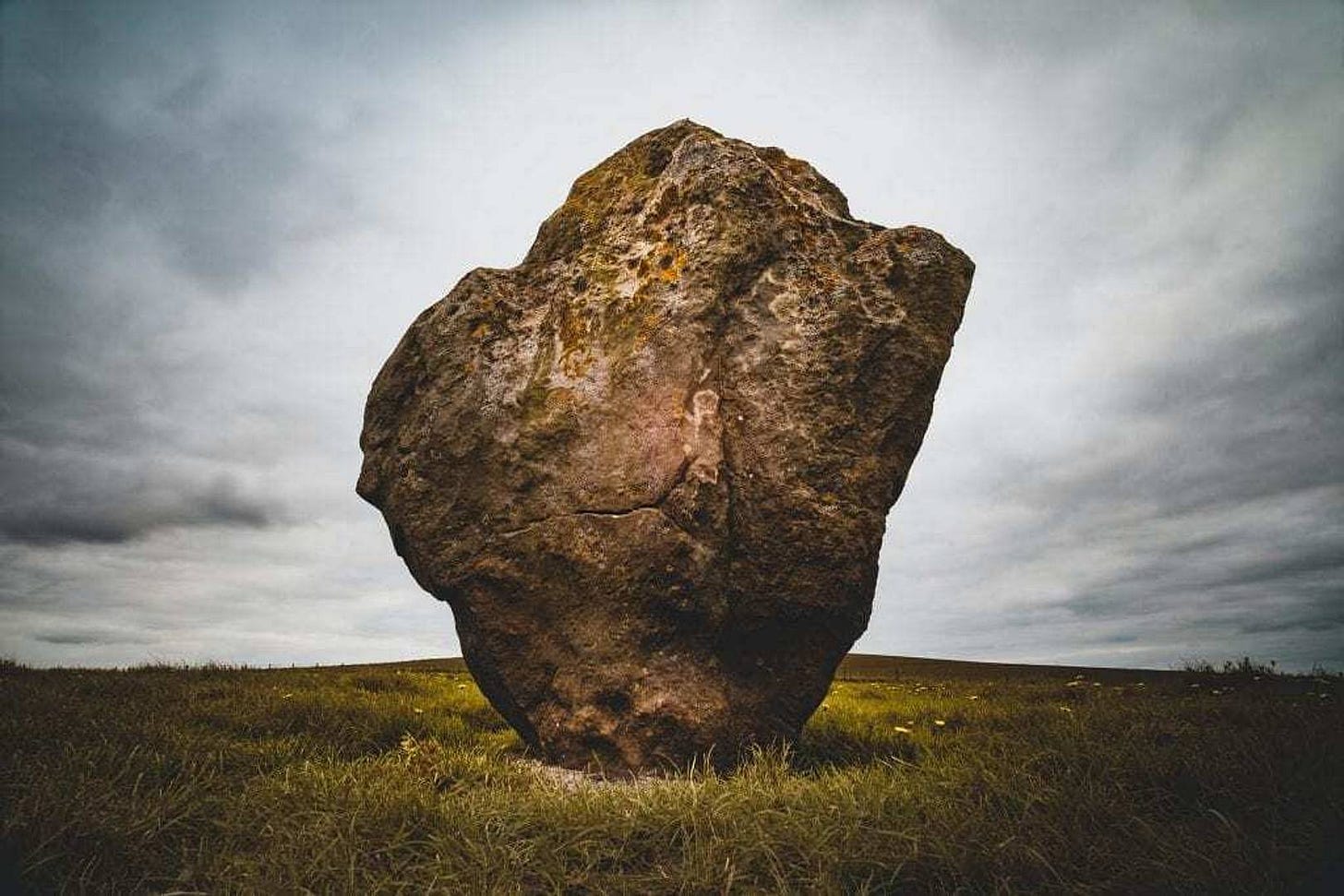

The second question is the same as the task of interpreting a metaphor, which is nothing else except apprehending “the another” from “the one”--e.g., apprehending that God supports from that he is rock.

The third question, for its part, is another mode of considering (colloquially speaking) what is the intellectual “path” from one to another: something bears us across to another–what route is taken?; something forthtells another–how does it do so?; something guides us beyond itself unto another–how is this done? This intellectual “path” also traces the ratio convenientiae, the explanation of fittingness which is unique to the metaphor.

For example, the metaphor that God is rock was fittingly put for that he supports, because e.g., just as a rock supports a house, just so God supports the universe. Indeed, there are many (and sometimes multiple) explanations of fittingness–metaphors have many “rationales behind the putting”--but this sort of explanation is most common and important. It is called analogy of proportionality, which involves a similitude of proportions or relationships of pairs: here, how “the one” regards something, is similar to how “the another” regards something else. The reason why this sort of explanation is most common, is because (as Thomas makes clear) our intellectual act of comparing pairs (i.e., of “doing” analogy of proportionality) is a “metaphor-making machine,” so to speak: in simple terms, whenever we compare pairs, we are inherently inclined to begin putting e.g., rock for supports, and to depict whatever supports as if it were a rock, now speaking metaphorically.

But Why Metaphors?: The Underlying Rationale

If this is what a metaphor is, we still need to consider the underlying rationale to its abundance throughout holy Scripture. If the prophets have used this tool so very much, then it is natural to question Why. To this question, we can respond generally and specifically, following Thomas.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Quodlibeta Theologica to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.