Senses of Holy Scripture: A Basic Intro from Thomas Aquinas

What are the senses of holy Scripture, and how are they distinguished from each other?

Doctrine about the many and different senses found in holy Scripture has been notoriously confused for several centuries, and most especially (it seems) among Protestant theologians. Two notable reasons for the latter are (1) that Protestants were especially afraid of “allegory,” given new pressures upon the letters of holy Scripture; and (2) that many theologians, particularly in Presbyterian/Reformed strains, pitted themselves against "many” senses or any senses beyond the “literal”—cf., WCF 1.1, and/or William Whitaker for a beginning here. (Whether and/or how this can be remedied, must remain for another time.) But at any rate, this general confusion has caused remarkable problems in confronting the phenomenon (for lack of better terms) of holy Scripture, and trying to do it justice. And this leads us to the questions,

What are the senses of holy Scripture, and how are they distinguished from each other?

One of the best scholastic expositors here is (you guessed it) Thomas Aquinas, who handles this and related questions in several places of his opera. His ST I q 1 a 10 is most commonly known, but another text stands out, namely his Galatians 4 commentary (Super Gal c 4 lect 7). There, while giving the sense of Galatians 4, Thomas stops to summarize the doctrine as a whole. He is prompted to do so not only given the difficulty of the current Galatian letter wherein we find may senses, including literal and spiritual; but also by the apostle’s claim that spiritual sense is in the Old Testament scriptures: “these were said allegorically.” Allegory, of course, is a highly equivocal name–not only in Paul’s time, but also (and perhaps more so) in Thomas’s. Accordingly, Thomas gives its sense here, and in the process explains the basics of the doctrine as a whole. For him, the following is what every theologian absolutely must know if he is to interpret any letter of holy Scripture:

There are two significations: one is through words, and the other is through realities which the words signify. This occurs not in other writings, but uniquely in holy Scripture, seeing that its author is God—God, in whose power it is to employ not just words for designating something (which even a man can do), but even realities themselves. Accordingly, in other sciences delivered by men, only words signify, as not except words can be employed for signifying; but unique to this [divine] science is that both words and realities themselves, which were signified through the words, signify something. Thus this science can have many senses–for that signification how words signify something, pertains to the literal (or historical) sense; whereas that signification how realities (signified by words) signify still other realities, pertains to the mystical sense.

Now on the one hand, something can be signified through the literal sense in two ways: namely, according to the propriety of some locution–as when I say that a man laughs; or according to a similitude/metaphor, as when I say that a field laughs. And holy Scripture uses both, as when we say that Jesus ascends (regarding the first mode), versus when we say that he sits at the right hand of God (regarding the second). Accordingly, under the literal sense is included the parabolic or metaphorical sense.

But on the other hand, the mystical (or spiritual) sense is divided into three. This is because, first, the old law is a figure of the new law–as the apostle says. Thus, insofar as those realities which are of the old law signify these realities which are of the new, we find the allegorical sense. Second, according to Dionysius (in his work, On Celestial Hierarchies), the new law is a figure of future glory. Thus, insofar as these realities which are in the new law and in Christ signify those realities which are in the fatherland, we find the anagogical sense. Third, also in the new law, those which are done in the head [namely, Christ], are examples of these which we ought to do, as whatsoever were written, were written for our learning. Thus, insofar as those realities which in the new law have been done either in Christ or in those [realities] which signify Christ are signs of these which we ought to do, we find the moral sense.

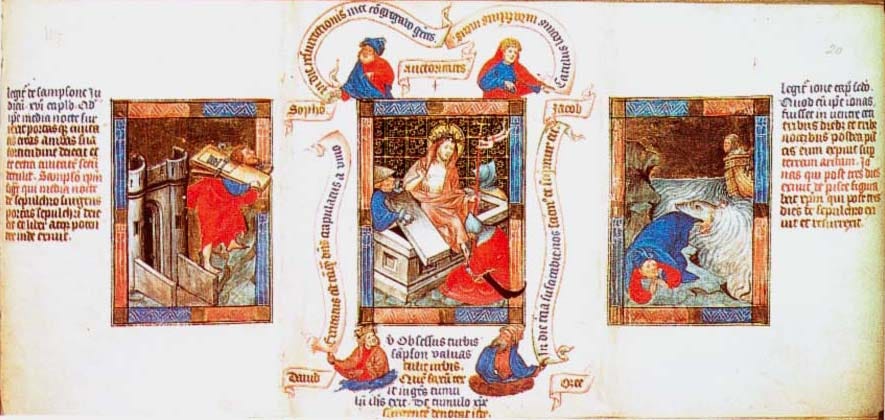

An example can clarify all these senses. Through the fact that I say let there be light ad litteram of bodily light, its sense reduces to the literal sense. But if this let there be light is understood i.e., let Christ be born in the church, then its sense reduces to the allegorical. Whereas if I said let there be light i.e., through Christ we are introduced to glory, then its sense reduces to the anagogical. But finally, if is said let there be light i.e., through Christ we are illumined in mind and inflamed in heart, then its sense reduces to the moral.

(My translation; the reader can consult Thomas’s text at aquinas.cc)

We want to carefully unpack this quotation and use it as our guide. Let’s begin with distinguishing Thomas’s two genera or overarching categories of sense, which are called literal and spiritual (or mystical). In following posts, we will then handle the two species of Thomas’s literal sense, and then also the three species of his spiritual.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Quodlibeta Theologica to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.